just one more thing

posted on

Sep 10, 2015 09:59AM

South Africa’s gold mines, the deepest and among the oldest in the world, are in big trouble.

The four largest producers in the country are losing money on about 35 percent of production at current prices, according to company data compiled by Bloomberg. At the same time, higher costs are cutting into profits as electricity bills climb to a record. Workers are also pushing for wage increases, with some threatening to strike if salaries aren’t doubled.

The nation, whose Witwatersrand Basin has supplied about a third of all gold ever mined, dropped from the top producer to sixth-biggest in just eight years. Now that miners who still crawl through tunnels using hand drills and dynamite have extracted much of the easy-to-dig metal, companies use modern technology to go deeper. That’s another expense, especially when bullion prices are near a five-year low.

“What you’re seeing in South Africa is a major margin squeeze,” Srinivasan Venkatakrishnan, chief executive officer of AngloGold Ashanti Ltd., the country’s biggest gold miner by market value, said in an interview. “If you do nothing, the future of South African gold mining always heads towards a declining trend.”

South African output slid at the fastest pace among the 10 biggest-producing countries in the past decade. Mine supply halved in the period to about 145 metric tons last year, according to the World Bureau of Metal Statistics.

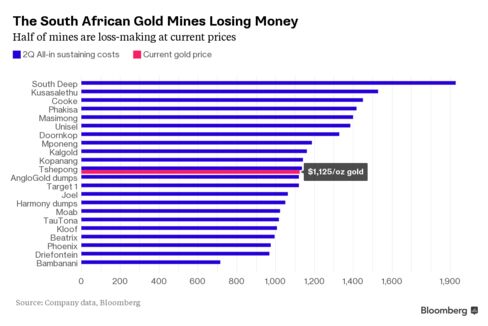

The metal has slumped 40 percent from its 2011 record to about $1,122 an ounce. At that price, half of mines owned by the nation’s top producers are losing money, data compiled from second-quarter financial reports show. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. has said bullion may go below $1,000.

The FTSE/JSE Africa Gold Mining Index is near the lowest since 2000, with Gold Fields Ltd., Sibanye Gold Ltd. and Harmony Gold Mining Co. falling at least 20 percent this year.

Electricity costs jumped 13 percent in April and power prices almost quadrupled since 2007 after underinvestment in new generation left an aging fleet of plants. Companies now face more pressure from workers who want wages to be as much as doubled, partly to account for dangerous working conditions they say haven’t changed much since the end of apartheid in 1994. Labor groups representing workers who go as far as 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) underground have rejected what’s been deemed a final pay offer.

“The unions want to get the best deal they can,” said Graham Briggs, CEO of Harmony Gold. “But when you’ve only got so much to give, then it’s up to the union leaders to understand: Where is that point? Where is that limit?"

Seven of Harmony’s 12 mines are losing money and it will gradually close three of its largest if cost cuts don’t make them profitable by year-end, Briggs said.

The weakest ever rand versus the dollar is cushioning South African producers that pay costs in the local currency and receive earnings in dollars. Gold priced in rand is the highest since 2012, making it economical for some producers to keep production going. Still, average local prices this quarter are little changed from the three months through June.

The industry has had to react before. Prices were lower than they are now in 2008, when the global financial crisis choked credit. AngloGold reported a net loss that year and cut spending while other companies reduced forward sales. Barrick Gold Corp., the world’s top producer, suffered a 22 percent plunge in profit that year and wrote down the value of its investments.

Newer projects, such as Gold Fields’s South Deep, are dealing with higher costs. The company has struggled to attract skilled workers to effectively run the country’s largest mechanized deep-level bullion mine since buying it for $3 billion in 2006. Production costs there were $1,900 an ounce in the second quarter, the highest among the top four companies.

The industry is stuck in a “time warp,” said Bruce Williamson, a former mine engineer who helps manage 2 billion rand at Imara Asset Management in Johannesburg. “Every time they tried to innovate, it would prove too difficult and too costly so they fell back on the low-cost, low-skill model.”

The problem is that low-cost mining is getting more expensive. Remuneration costs jumped 60 percent in the seven years to 2014 even as the number of employees dropped 30 percent, according to the Chamber of Mines, which represents companies. The two largest unions have rejected an offer to raise basic pay from about 6,000 rand a month and the National Union of Mineworkers has declared a dispute. A mediation process will start Sept. 14 and the NUM has said it can’t rule out a strike.

Without an agreement, South Africa’s gold industry will continue its decline, according to AngloGold’s Venkatakrishnan.

“What you’ll see is companies cutting short the life of mines,” he said.