BLACK SWANS, YELLOW GOLD

posted on

Nov 27, 2015 05:56PM

Black Swans, Yellow Gold

How gold performs during periods of deflation, chronic disinflation, runaway stagflation and hyperinflationby Michael J. Kosares

"The inability to predict outliers implies the inability to predict the course of history. . .But we act as though we are able to predict historical events, or, even worse, as if we are able to change the course of history. We produce thirty-year projections of social security deficits and oil prices without realizing that we cannot even predict these for next summer -- our cumulative prediction errors for political and economic events are so monstrous that every time I look at the empirical record I have to pinch myself to verify that I am not dreaming. What is surprising is not the magnitude of our forecast errors, but our absence of awareness of it."

- Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan -- The Impact of the Highly Improbable, 2010

"Having been mugged too often by reality, forecasters now express less confidence about our abilities to look beyond the immediate horizon. We will forever need to reach beyond our equations to apply economic judgment. Forecasters may never approach the fantasy success of the Oracle of Delphi or Nostradamus, but we can surely improve on the discouraging performance of the past."

- Alan Greenspan, The Map and the Territory, 2013

Introduction

This short study examines gold's performance under the four most commonly predicted worst-case economic scenarios -- a 1930s-style deflation, chronic Japanese-style disinflation, a 1970s-style runaway stagflation, and a Weimar-style hyperinflation. "That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history," Aldous Huxley once wrote, "is the most important of all the lessons of history." Though I agree with Huxley's assessment when applied to contemporary policymakers and central bankers, I do not agree with it when applied to their counterparts in the private sector, i.e., the individual investors. As justification, I offer the ongoing (and long-term) success of the USAGOLD website as well as the soaring statistics of late on private gold ownership both here and abroad. Individually, we can and do learn the lessons of history even if we do not always do so collectively.

Black Swans, Yellow Gold is dedicated to those who believe, like Nicholas Taleb, that it is just as important to prepare for what we cannot foresee as what we can. Some might put their money on the latest Oracle of Delphi or the contemporary reincarnation of Nostradamus -- or even an all-seeing eye plug-in that can be downloaded from the internet -- but in the end, such notions are the dreams of government planners and retired central bankers. For the rest of us, a solid hedge in gold coins, as your are about to read, is the more sensible and reliable alternative -- a wealth haven for all seasons.

A couple real-life experiences worth noting

Several years ago I did an appraisal for a client who was pledging his gold as collateral in a commercial real estate transaction. In the course of doing the appraisal, I was impressed with the large gain in value. His original purchase in 2002 was in the seven figures when gold was still trading in the $300 range. His holdings had appreciated 50% after a roughly three-year holding period. (Since that appraisal, the value has risen another nearly three times at this writing.) I asked his permission tell his story at our website as an example of how gold can further one's business plans.

"No problem at all," he wrote by return e-mail, "I have viewed it as a hedge, but also as an alternative to money market funds. Now I can leverage it for investment purposes -- private equity and real estate mostly. The holding has averaged 7%-10% of my total assets. And I do hope to buy substantially more, when appropriate. Thanks again."

It needs to be emphasized that he was not selling his gold, but pledging it as collateral to finance other aspects of his business. Selling it would have meant giving up his hedge -- something he didn't want to do. Instead, he was using gold to further his business interests in a transaction in which he would become a principal owner.

Upon publishing his story at the USAGOLD website, we received a letter from another client with a similar story to tell:

"I read the article in the newsletter about one of your clients buying 1 million of gold four years ago and it now being worth $1.5 million. I have a similar true story if you would like to use it. About four years ago, I talked my father into converting about a third of his cash into gold, mostly pre-33 British Sovereigns. I bought for him from USAGOLD approximately $80,000 when spot gold was about $290 per ounce. He had the rest of his money in 1-2% CDs in the bank. My father passed away recently and I am executor. He willed my brother $250,000 which was essentially all of his gold and cash. I gave my brother the gold along with the bank CDs. While the CDs had earned barely a pittance in those 4 years the gold had become 41% more valuable.

"So instead of receiving $250,000 my brother really received about $282,800 ($80,000 x 141% = $112,800 or + $32,800). Had my father converted all his paper money to gold my brother would have received $352,500. Ironically my father was very conservative and didn't like to gamble. In this case his biggest gamble was watching those CDs smolder and not acquiring real money -- gold."

(Author's note: Today this client's holdings have nearly tripled in value again to nearly $350,000 -- even after gold's most recent correction. A modest inheritance has become quite valuable.)

It is interesting to note that both clients view their gold as a savings and safe haven instrument as opposed to an investment for capital gains -- a viewpoint very different from the way gold is commonly portrayed in the mainstream media. An interesting side note to their successful utilization of gold is that it occurred in the predominantly disinflationary environment of the "double-ought" decade (from 2000-2013) when inflation was moderate -- a counter-intuitive result covered in more detail below.

Now, as the economy has gotten progressively worse, many investors are beginning to ask about gold's practicality and efficiency under more dire circumstances -- the ultimate black swan, or outlier event like a deflationary depression, severe disinflation, runaway stagflation or hyperinflation. The following thumbnail sketches draw from the historical record to provide insights on how gold is likely to perform under each of those scenarios.

Gold as a deflation hedge (United States, 1929)

WEBSTER DEFINES DEFLATION AS A "CONTRACTION IN THE VOLUME of available money and credit that results in a general decline in prices." Typically deflations occur in gold-standard economies when the state is deprived of its ability to conduct bailouts, run deficits and print money. Characterized by high unemployment, bankruptcies, government austerity measures and bank runs, a deflationary economic environment is usually accompanied by a stock and bond market collapse and general financial panic -- an altogether unpleasant set of circumstances.

The Great Depression of the 1930s serves as a workable example of the degree to which gold protects its owners under deflationary circumstances in a gold standard-economy. First, because the price of gold was fixed at $20.67 per ounce, it gained purchasing power as the general price level fell. In 1933, when the U.S. government raised the price of gold to $35 per ounce in an effort to reflate the economy through a formal devaluation of the dollar, gold gained even more purchasing power.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt also seized gold bullion by executive order in concert with the devaluation, but exempted "rare and unusual" gold coins which later were defined by regulation simply as items minted before 1933. As a result, only those citizens who owned gold coins dated before 1933 were able to reap the benefit of the higher fixed prices. The accompanying graph illustrates those gains, as well as as the gap between consumer prices and the gold price.

Figure 1 - Gold as a deflation hedge

Second, since gold acts as a stand-alone asset that is not another's liability, it functioned as an effective store of value prior to 1933 for those who either converted a portion of their capital to gold bullion or withdrew their savings from the banking system in the form of gold coins before the crisis struck. Those who did not have gold as part of their savings plan found themselves at the mercy of events when the stock market crashed (in 1929) and the banks closed their doors (many of which had already been bankrupted).*

How gold might react in a deflation under today's fiat money system is a more complicated scenario. Even deflation under a fiat money system, the general price level would be falling by definition. Economists who make the deflationary argument within the context of a fiat money economy usually use the analogy of the central bank "pushing on a string." It wants to inflate, but no matter how hard it tries the public refuses to borrow and spend. (If this all sounds familiar, it should. This is precisely the situation in which the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank find themelves today.) In the end, so goes the deflationist argument, the central bank fails in its efforts and the economy rolls over from recession to a full-blown deflationary depression.

How governments treat gold under a deflationary scenario will play heavily into its performance:

- If gold is subjected to official price controls, as it was in the 1930s deflation, it would likely perform as it did then, i.e., its purchasing power would increase as the price level fell.

- If not subjected to price controls, it would turn out to be the best of all possible worlds for gold owners. Its purchasing power would increase as the price level fell, and the price itself could rise as a result of increased demand from investors hedging systemic risks and financial market instability.**

The disinflationary period leading up to and following the financial market meltdown of 2008 serves as a good example of how a deflationary scenario might unfold. The disinflationary economy is a close cousin to deflation, and is covered in the next section. It provides some solid clues as to what we might expect from gold under a full deflationary breakdown.

____________

* In practice only a small percentage of investors actually benefited from gold's increased purchasing power as illustrated in the chart above. Even before Roosevelt's actions in 1933, most nation states in Europe had already withdrawn gold coins from circulation and introduced irredemable paper money as a substitute. In keeping with Gresham's Law (Bad money drives out good), large quantities of gold coins and bullion quickly disappeared into the private hoards of wealthy individuals, families and financiers. This group, though small in number, obviously benefited from the formal devaluation of national paper currencies against gold during the 1930s as central banks expanded credit and currency issue to combat the Great Depression (just as they are today to combat the current Great Recession). Nation states continued to hold gold in their national treasuries to varying degrees and settled payment imbalances between each other in gold bullion and coin. As a result, the official sector became probably the most direct and visible beneficiary of gold's increased purchasing power at $35 per ounce. In the United States (as mentioned immediately above), only those citizens who held the exempted gold coins minted before 1933 gained that benefit.

Side note: The withdrawal of gold from circulation on a global basis set the stage for its replacement by the U.S. dollar standard after World War II. Under the Bretton Woods Agreement (1944), all the major currencies traded at a fixed rate to the dollar and the dollar, for redemption purposes, was fixed at 1/35th of an ounce of gold among nation states. That benchmark (and the agreement) broke down in the early 1970s when the Richard Nixon administration, in an effort to protect U.S. gold reserves severed the tie between gold and the dollar, closed the international gold redemption window and suspended the fixed exchange rate between the dollar and the rest of the world's currencies. These actions launched the current fiat money era. Gold was later re-legalized in the United States (1975) providing impetus to the contemporary private gold market where many among the world's citizenry hedge their concerns about the future value of irredeemable national currencies through private gold coin and bullion ownership.

Gold as a disinflation hedge (United States, 2008)

JUST AS THE 1970s REINFORCED GOLD'S EFFICIENCY as a stagflation (combination of economic stagnation and inflation) hedge in the modern era, the 2000's decade solidly established gold's credentials as a disinflation hedge. Disinflation is defined as a decrease in the inflation rate over time (or a constantly low inflation rate), and should not be confused with deflation, which is an actual drop in the price level. Disinflations, as pointed out above, are close cousins to deflations and can evolve to that if the central bank fails, for whatever reasons, in its stimulus program. Central banks today are activist by design. To think that a modern central bank would sit back during a disinflation and let the chips fall where they may is to misunderstand its role. It will attempt to stimulate the economy by one means or another. The only question is whether or not it will succeed.

Up until the "double oughts," the manual on gold read that it performed well under inflationary and deflationary circumstances, but not much else. However, as the decade of asset bubbles, financial institution failures, and global systemic and sovereign debt risk progressed, gold marched to higher ground one year after another. As events unfolded, it became increasingly clear that the metal was capable of delivering the goods under disinflationary circumstances as well. The fact of the matter is that during the 2000s even as the inflation rate hovered in the low single digits, gold managed to rise from just under $300 per ounce in the early 2000s to just over $1900 per ounce by 2011 -- a gain of over 600%. Since then, gold has taken a breather. As this essay is written, it is trading in the $1250 per ounce range -- still up over 400% in the new century.

In the aftermath of the 2008-2007 financial crisis, something else happened to the yellow metal: It firmly re-established itself with private investors and nation-states as perhaps the ultimate asset of last resort. As the economy flirted with a tumble into the deflationary abyss in recent years, it encouraged the kind of behavior among investors that one might have expected in the early days of a full deflationary breakdown with all the elements of a financial panic. Stocks tumbled. Banks teetered. Unemployment rose. Mortgages went into foreclosure. Nation-states defaulted on their debts. Disinflation globally became chronic and debilitating.

Figure 2 - Gold as a disinflation hedge

As it became evident that the economic and financial malaise could become a permanent fixture (the new normal), gold came under accumulation globally. In 2009, U.S. Gold Eagle sales, a bellwether for public interest in the metal, broke all records by a wide margin, and the pace of accumulation has remained at high levels ever since. The world's central banks, historically at odds with each other with respect to currency policies, have teamed up to deliver ever larger doses of monetary stimulus that goes far beyond ordinary tinkering with interest rates. Money printing has become a global undertaking -- a phenomenon the consequences of which are yet to be determined.

Meanwhile, the disinflationary crisis that began in 2008-2007 is still with us and, through it all, gold demand has not only gone undeterred. Although many thought the price correction would dampen interest, the opposite has happened: It encouraged a new wave of investment interest particularly in the Far East where low prices were greeted with a wave of public demand. In 2013, China reportedly imported nearly the equivalent of the world's annual gold mine output -- almost 2700 tonnes - and other emerging and developed nation-states alike have experienced their own versions of a new gold rush.

All in all, as the graph immediately above demonstrates, the first decade of the 21st century ushered in a new era for gold, one in which it filled a hole in its resume. Now gold has come to be viewed as an effective hedge against one of contemporary economies' most nettlesome problems -- chronic disinflation and the systemic financial risks it periodically imposes.

Gold as a hyperinflation hedge (France, 1790s)

ANDREW DICKSON WHITE ENDS HIS CLASSIC HISTORICAL ESSAY on hyperinflation, "Fiat Money Inflation in France," with one of the more famous lines in economic literature: "There is a lesson in all this which it behooves every thinking man to ponder." The lesson that there is a connection between government over-issuance of paper money, inflation and the destruction of middle-class savings has been routinely ignored in the modern era. So much so, that enlightened savers the world over wonder if public officials will ever learn it.

ANDREW DICKSON WHITE ENDS HIS CLASSIC HISTORICAL ESSAY on hyperinflation, "Fiat Money Inflation in France," with one of the more famous lines in economic literature: "There is a lesson in all this which it behooves every thinking man to ponder." The lesson that there is a connection between government over-issuance of paper money, inflation and the destruction of middle-class savings has been routinely ignored in the modern era. So much so, that enlightened savers the world over wonder if public officials will ever learn it.

White's essay tells the story of how good men -- with nothing but the noblest of intentions -- can drag a nation into monetary chaos in service to a political end. Still, there is something else in White's essay -- something perhaps even more profound. Democratic institutions, he reminds us, well-meaning though they might be, have a fateful, almost predestined inclination to print money when backed against the wall by unpleasant circumstances.

If there is a hyperinflationary shock in the United States, the opening salvo would probably be a sudden undermining of the dollar's status as the world's reserve currency. Up until recently, the United States enjoyed a strong world-wide demand for its government paper. Thus, the negative effects of government deficits have been subdued. Now, with consistently low interest rates and a growing fear globally that U.S. deficits may have run out of control, foreign support for the U.S. bond market has faltered. In the absence of international buyers, the Fed already has been forced to monetize an ever larger portion of the debt -- the modern equivalent of printing money. Whether or not it can follow through on its promise to reduce government bond purchases in the face of lagging foreign demand remains an open question.

Though the global demand for dollars remains the principal factor standing between relative calm and monetary mayhem, an inflationary surprise could come from another direction entirely. With nation-states around the world engaged acutely in the money printing game (and in deadly competition with one another), one cannot rule out the possibility of a generalized global descent into the inflationary abyss -- at first slowly, then more rapidly until a large portion of the world's population awakens one day to a global hyperinflationary breakdown.

Episodes of hyperinflation ranging from the first (Ghenghis Khan's complete debasement of the very first paper currency) through the most recent (the debacle in Zimbabwe) all start modestly and progress almost quietly until something takes hold in the public consciousness that unleashes the pent-up price inflation with all its fury. Frederich Kessler, a Berkeley law professor who experienced the 1920s nightmare German Inflation first-hand, gave this description some years later during an interview published in Ralph Foster's book, "Fiat Paper Money: The History and Evolution of Our Currency" (2008): "It was horrible. Horrible! Like lightning it struck. No one was prepared. You cannot imagine the rapidity with which the whole thing happened. The shelves in the grocery stores were empty. You could buy nothing with your paper money."

Towards the end of "Fiat Money Inflation in France," White sketches the price performance of the roughly one-fifth ounce Louis d' Or gold coin:

Towards the end of "Fiat Money Inflation in France," White sketches the price performance of the roughly one-fifth ounce Louis d' Or gold coin:

"The louis d'or [a French gold coin weighing.1867 net fine ounces] stood in the market as a monitor, noting each day, with unerring fidelity, the decline in value of the assignat; a monitor not to be bribed, not to be scared. As well might the National Convention try to bribe or scare away the polarity of the mariner's compass. On August 1, 1795, this gold louis of 25 francs was worth in paper, 920 francs; on September 1st, 1,200 francs; on November 1st, 2,600 francs; on December 1st, 3,050 francs. In February, 1796, it was worth 7,200 francs or one franc in gold was worth 288 francs in paper. Prices of all commodities went up nearly in proportion. . .

Examples from other sources are such as the following -- a measure of flour advanced from two francs in 1790, to 225 francs in 1795; a pair of shoes, from five francs to 200; a hat, from 14 francs to 500; butter, to, 560 francs a pound; a turkey, to 900 francs. Everything was enormously inflated in price except the wages of labor. As manufacturers had closed, wages had fallen, until all that kept them up seemed to be the fact that so many laborers were drafted off into the army. From this state of things came grievous wrong and gross fraud. Men who had foreseen these results and had gone into debt were of course jubilant. He who in 1790 had borrowed 10,000 francs could pay his debts in 1796 for about 35 francs."

Those two short paragraphs speak volumes of gold's safe-haven status during a tumultuous period and may raise the most important lesson of all to ponder: the roll of gold coins in the private investment portfolio.

Most Americans take the attitude that "it can't happen here", but the truth of the matter is that no economy or monetary system is immune to the ultimate effects of printing too much money. "Like previous hyperinflations throughout time," says Patrick Barron, an economics professor at Wisconsin University's Graduate School of Banking in a paper published at the Ludwig von Mises Instiutite, "the actions that produce an American hyperinflation will be seen as necessary, proper, patriotic, and ethical; just as they were seen by the monetary authorities in Weimar Germany and modern Zimbabwe. Neither the German nor the Zimbabwean monetary authorities were willing to admit that there was any alternative to their inflationist policies. The same will happen in America." The official mindset that unleashes the hyperinflation is already present in U.S. monetary policy and to think it might be suddenly brought to heel could become the source of our undoing. History tells us that once the inflationary genie is out of the bottle, it is difficult to get it back in.

Gold as a runaway stagflation hedge (United States, 1970s)

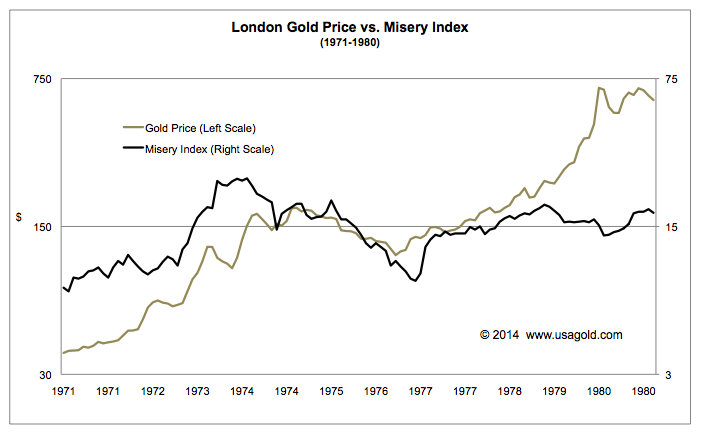

IN THE CONTEMPORARY GLOBAL FIAT MONEY SYSTEM, when the economy goes into a major tailspin, both the unemployment and inflation rates tend to move higher in tandem. The word "stagflation" is a combination of the words "stagnation" and "inflation." President Ronald Reagan famously added unemployment and inflation together in describing the economy of the 1970s and called it the Misery Index. As the Misery Index moved higher throughout the decade so did the price of gold, as shown in the graph immediately below.

Figure 3 - Gold as a stagflation hedge

At a glance, the chart tells the story of gold as a runaway inflation/stagflation hedge. The Misery Index more than tripled in that ten-year period, but gold rose by nearly 16 times. Much of that rise has been attributed to pent-up pressure resulting from many years of price suppression during the gold standard years when gold was fixed by government mandate. Even after accounting for the fixed price, it would be difficult to argue that gold did not respond readily and directly to the Misery Index during the stagflationary 1970s.

In a certain sense, the U. S. experience in the 1970s was the first of the runaway stagflationary breakdowns, following President Nixon's abandonment of the gold standard in 1971. Following the 1970's U.S. experience, similar situations cropped up from time to time in other nation-states. Argentina (late 1990s) comes to mind, as does the Asian Contagion (1997), and Mexico (1986). In each instance, as the Misery Index rose, the investor who took shelter in gold preserved his or her assets as the crisis moved from one stage to the next.

Fortunately, the 1970's experience in the United States was relatively moderate by historical standards in that the situation fell short of escalating to either a deflationary or hyperinflationary breakdown. These lesser events, however, quite often serve as preludes to more severe and debilitating events at some point down the road. All in all, it is difficult to classify stagflations of any size and duration as insignificant to the middle class. Few of us would gain comfort from the fact that the Misery Index we were experiencing failed to transcend the 100% per annum threshold or failed to escalate to a state of hyperinflation and deflation. Just the specter of a double-digit Misery Index is enough to provoke some judicious portfolio planning with gold serving as the hedge.

A portfolio choice for all seasons

"An ounce of gold cost $271 in 2001. Ten years later it reached $1,896—an increase of almost 700 percent. On the way, it passed through some of the stormiest periods of recent history, when banks collapsed and currencies shivered. The gold price fed on these calamities. In a way, it came to stand for them: it was the re-discovered idol at a time when other gods were falling in a heap of subprime mortgages and credit default swaps and derivative products too complicated to even understand. Against these, gold shone with the placid certainty of received tradition. Honored through the ages, the standard of wealth, the original money, the safe haven. The value of gold was axiomatic. This view depends on a concept of gold as unchanging and unchanged—nature's hard asset." - Matthew Hart, Vanity Fair, November, 2013

A BOOK COULD BE WRITTEN ON THE SUBJECT OF GOLD AS A HEDGE against the various 'flations. I hope the short sketches just provided will serve at least as a functional introduction to the subject. The conclusion is clear: History shows that gold, better than any other asset, protects the portfolio against the range of ultra-negative economic scenarios, such so-called black swan, or outlier, events as deflation, chronic disinflation, runaway stagflation or hyperinflation.

Please note that I was careful not to favor one scenario over the other throughout this essay. The argument as to which of these maladies is most likely to strike the economy next is purely academic with respect to gold ownership. A solid hedge in gold protects against all of the disorders just outlined and no matter in which order they arrive.

I would like to close with a thoughtful justification for gold ownership from a UK parliamentarian, Sir Peter Tapsell. He made these comments in 1999 after then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, forced the auction sale of over half of Britain's gold reserve. They get to the heart of the matter and are as relevant today as they were when they were first spoken. Tapsell's reference to "dollars, yen and euros" has to do with the British treasury's proposal to sell the gold reserve and convert the proceeds to "interest bearing" instruments denominated in those currencies. Though he was addressing gold's function with respect to the reserve of a nation-state (the United Kingdom), he could have just as easily been talking about gold's role for the private investor:

"The whole point about gold, and the quality that makes it so special and almost mystical in its appeal, is that it is universal, eternal and almost indestructible. The Minister will agree that it is also beautiful. The most enduring brand slogan of all time is, 'As good as gold.' The scientists can clone sheep, and may soon be able to clone humans, but they are still a long way from being able to clone gold, although they have been trying to do so for 10,000 years. The Chancellor [Gordon Brown] may think that he has discovered a new Labour version of the alchemist's stone, but his dollars, yen and euros will not always glitter in a storm and they will never be mistaken for gold."

These words are profound. They capture the essence of gold ownership. In the nearly one and a half decades since the British sale, gold went from $300 per ounce to over $1900 per ounce at what many believe to be its interim high -- making a mockery of what has come to be known in Britain as Brown's Folly. The "dollars, yen and euros" that the Bank of England received in place of the gold have only continued to erode in value while paying a negligible to non-existent return. And most certainly they have not glittered in the storm. What would the conservative government of David Cameron give to have that 415 tonnes of gold back as it introduces austerity measures in Britain and attempts to undergird the value of the British pound?

Returning to the stories told at the top of this essay, these are just two accounts among thousands that could be swapped among our clientele. I receive calls regularly from what I like to call the "Old Guard" -- those who bought gold in the $300s, $400s and $500s, even the $600s. Many had read The ABCs of Gold Investing: How to Protect and Build Your Wealth with Gold. Some have become very wealthy as a result of those early purchases. The most important result though is that these clients managed to maintain their assets at a time when others watched their wealth dissipate. Gold has performed as advertised -- something it is likely to continue doing in the years ahead. After all is said and done, as I wrote in The ABCs many years ago, gold is the one asset that can be relied upon when the chips are down. Now more than ever, when it comes to preserving assets, gold remains, in the most fundamental sense, the portfolio choice for all seasons.

_______________________________________________________________________________