metals trading has a paper fraud problem

posted on

Jul 04, 2017 04:27PM

NI 43-101 Update (September 2012): 11.1 Mt @ 1.68% Ni, 0.87% Cu, 0.89 gpt Pt and 3.09 gpt Pd and 0.18 gpt Au (Proven & Probable Reserves) / 8.9 Mt @ 1.10% Ni, 1.14% Cu, 1.16 gpt Pt and 3.49 gpt Pd and 0.30 gpt Au (Inferred Resource)

For all the high-tech wizardry of modern financial markets, there’s one corner of the commodity world that still depends almost entirely on printed paper -- making it an easy target for crooks.

Buyers and sellers of base metals like copper, aluminum and nickel use documents known as warehouse receipts to prove every pound involved in a transaction actually exists and who owns it. The receipts, from a long list of issuers who often stamp them with holograms and secret codes, have become the linchpin of bank loans backed by the metal as collateral.

But like most pieces of paper, warehouse receipts can be faked, and there are signs that more lenders are being ripped off by crooks exploiting weaknesses in what commodity businesses refer to as trade financing. For the second time since 2014, some banks are facing multimillion-dollar losses after being tricked into making loans secured by goods that didn’t exist.

“It’s a pervasive problem,” said John Barlow, a partner at Holman Fenwick Willan LLP who advises insurers of banks on risks including trade financing. “There’s an inherent risk in transacting business in this way, and banks face the choice of either accepting that risk, or completely restructuring the way the industry operates,” he said by phone from Dubai.

Lending against commodities sitting in a warehouse somewhere is a bread-and-butter business for banks involved in trade finance, a $4 trillion industry spanning everything from commodities, logistics and shipping. Producers and traders use the deals as a way to quickly get cash by temporarily pledging inventories. Given the global inventory at risk, the incidence of fraud remains relatively rare.

However, warehouse receipts are a favorite target of commodity fraudsters. French lender Natixis SA and Melbourne-based Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd.are facing loan losses after discovering fake documents used to verify nickel stored in Asian warehouses owned by Access World, a subsidiary of Glencore Plc. The deals involved $305 million for ANZ and $32 million to Natixis, according to court filings this year.

A spokesman for ANZ said the bank’s exposure was accounted for as a non-material item in its first-half results and was significantly less than the value of the contract. ANZ’s standard documents provide recourse for ANZ in the event of fraud, he said in an emailed statement. He wasn’t immediately able to comment on how the exposure had been reduced.

Natixis, Marex and Glencore declined to comment.

It’s not clear from the court records who is accused of orchestrating the alleged frauds. But Natixis is suing broker Marex Financial Ltd., which responded by saying the receipts were checked and verified as genuine, according to legal papers filed in London. Marex argues Access World should be liable for any losses because it authenticated the documents.

ANZ has hired lawyers in the U.S., Hong Kong and Singapore to attempt to recover its losses and pursue the alleged fraudsters. When ANZ looked into selling the nickel, it discovered 83 out of 84 receipts were likely forgeries, the lender said in a June 6 petition filed in a U.S. court in San Francisco.

See also: ANZ Suffered ‘Substantial Losses’ in Nickel Receipts Scam

This isn’t the first time that banks have been caught out by a major financing scam in commodities. In 2014, Standard Chartered Plc, Citigroup Inc. and Standard Bank Group Ltd. revealed almost $648 million of fraud involving copper, aluminum and alumina stored in the Chinese port of Qingdao that had been used to raise finance multiple times.

Lawsuits are just the tip of the iceberg, Barlow said. There are more disputes over fraudulent title documents in arbitration proceedings around the world, he said.

While banks and warehouses have taken steps to limit counterfeiting since then, the reliance on paper documentation means the business remains inherently risky, Barlow said.

One problem is that there’s no standardized way of tracking and verifying inventories. The London Metal Exchange, the industry pricing benchmark, oversees a network of more than 600 warehouses and manages a central system. But the LME represents only a small part of all the metal bought and sold, mostly because its fees are higher than private storage depots, and the bourse is more heavily regulated. The LME also has no warehouses in China.

For example, warehouses monitored by the LME and the Shanghai Futures Exchange hold a combined 1.8 million tons of aluminum valued at $3.5 billion at today’s prices. There could be 10 million tons or more of additional inventory in private storage around the world, according to some industry estimates.

Another issue is that a single transaction may require keeping track of as many as 40 original documents, said Angelique Slach, chief innovation officer for trade and commodity finance at Cooperatieve Rabobank UA. Switching to a digital system would save time and cut costs, she said.

“If all parties are using the same systems, document handling might take a couple of hours, rather than a couple of weeks,” Slach said.

In the recent Natixis and ANZ case, banks paid for a professional courier to fly from Singapore to London to hand deliver the warehouse receipts for inspection, according to Marex court filings. The documents, which passed inspection, were later found to be fake.

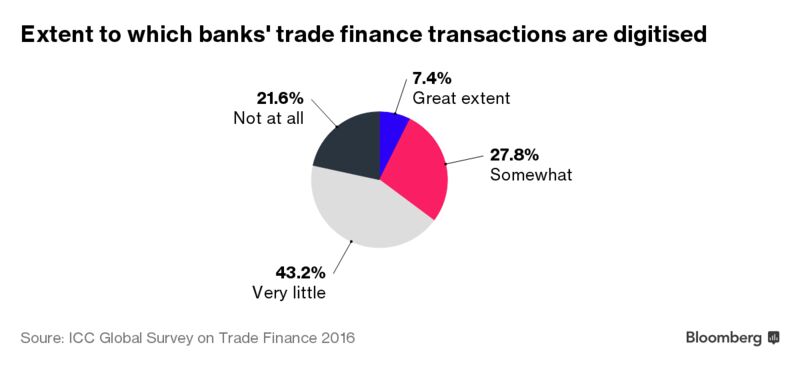

There are some signs that the industry is moving toward a distributed database known as a blockchain that would improve the way ownership is verified. In March, Natixis teamed up with commodity trader Trafigura BV and information technology developer IBM Corp. to set up a system backed by a digital ledger. The platform would be open to all users and any attempt to alter an invoice or use a document more than once would be obvious to all participants.

“The current process is paper and labor intensive,” Arnaud Stevens, Natixis’s New York head of global energy and commodities, said in March when the platform project was announced.

A similar system is already taking shape in the iron ore market. Major shippers including Vale SA and BHP Billiton Ltd., banks such as ING Groep NV and Westpac Banking Corp., and traders like Cargill Inc. and Glencore signed up for a paperless shipment-management system called essD0CS. A previous Morgan Stanley trading unit -- now part of Castleton Commodities -- was one of the first users of the platform, a spokesman said.

The LME is also expanding its system to monitor metal as it moves from its warehouses to depots outside the system. The exchange says the enhancement will help to “safeguard against multiple claims of ownership.”

Trades backed up by digitally authenticated documents will start within the next year, with blockchain systems steadily increasing over the next decade before they become dominant in the industry, according to Rabobank’s Slach. They improve security, reduce costs and speed up deals.

But these systems may not gain widespread use until a digital standard emerges for creating and sharing documents, Holman Fenwick Willan’s Barlow said.

“Transferring documents electronically is probably the way forward,” he said. “It’s the inefficiency of the current system that means the problem continues.”

In the meantime, insurers are reviewing how to offer the industry better protection against losses. After Qingdao, Marsh Ltd. began offering the option for additional coverage against document fraud, said Craig Glendinning, a senior vice president at the firm.

“The risk has always been present, and over time the industry has adapted by adopting controls and procedures to hold fraud in check,” Glendinning said by email. “However, we are now seeing a material increase in both the frequency and severity of documentary fraud.”